Photography © Debbie Bragg

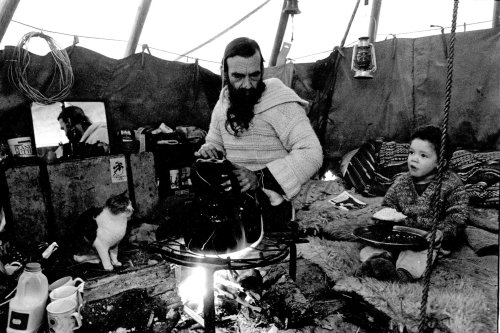

The tipis, the settlers and the quest for a better life are all reminiscent of the Wild West – but this west Wales not Wyoming. The dome-shaped huts are part of what is known as Tipi Valley, recognized as the UK’s first eco-communities, based in what most Brits would call the back of beyond. Even the nearest town Llandeilo is medieval and Tipi Valley is a really live up to the principles of back to basics.

A middle-aged woman with a French twist in her hair is hanging out the washing. "Welcome", she exclaims smiling broadly.

Tipis dot the hillside like raisins on a cake in the morning sun. Hidden in a lush green valley and far away from the hustle and bustle of Llandeilo, Tipi village stands right where the countryside opens out. It is quiet and the world, as you know it far away.

Tipi Village

the biggest of all UK eco-communities was founded in 1976, and is home to families with three generations. Most are permanent residents, living in low impact dwellings, from tipis, yurts, and caravans, to roundhouses. A small number, usually the elders, after many years in a tipi, have moved to live in cottages.

They are not the first people to use tipis. The American Indians of the Great Plain Tipi used tipis (known also as teepee, tepee) and nowadays, tipis are a familiar sight at indie music festivals. Most of the tipi people are British, constitute from families, to activists, original hippies, festival junkies, and musicians.

nATURE

is not gentle nor always kind at the Tipi village. The wind slaps against the epic Welsh mountains (near the hamlet of Cywmdu). Seemingly endless rainstorms, which leave everyone mud splattered seem to go unnoticed. They are certainly in touch with the earth - quite literally.

Their breakaway to establish an alternative lifestyle isn’t new either, nor the long arduous search of it. Yet historically, Ulysses, for example was always trying his best to come home. Unlike him, these new wanderers are off on an escapade toward an unknown lifestyle.

“There are more than 100 tipi tents across the cliff side. Unlike other similar communities, Tipi villagers do not require quests to pre-book and do not expect them to work. There is no charge. Visitors welcomed and encouraged to give this lifestyle a try. ”

Enter the tipi

Visitors are free to stay in the valley, sleeping in Big Lodge, a large Tipi erected on a green slope on the edge of the valley.A wild-haired ten-year-old boy called Keisha, offers to guide us to the Big Lodge, which is the site’s guest tipi. He wants to visit this year’s Glastonbury Festival and due to that he has been keeping his fingers with a sticky tape crossed for a month. As he lifted up the canvas ‘ door ’, we dived quickly inside to find fellow guest Tony wrapped in his sleeping bag. The rules of the Big Lodge are quite simple, such as: ‘Take your shoes off before entering a dwelling’, which rings a bell that life isn’t so different from a normal suburban home. As rain begins to fall we finally introduce ourselves to Tony over the dreamy glow of a fiercely and noisily burning fire. He looks tanned, strong, healthy. He is a long-term guest, "who plans to settle down in there with his girlfriend". To thank Keisha, we offered him some of the chocolates, but he took just one. "This is enough", he tells us and then, he disappears.

Tipis are durable dwellings, which offer warmth or cool, depending on the season, and comfort to its inhabitants. Inside every tipi, space is used wisely. Bedding is rolled up during the day. The ground is often covered with woven material. Instead of sofas there are sheepskins to sit on. A marked characteristic of the tipi is that, it has central heating literally. It is designed to host an indoor fire. All in all, you can heat the water and for cooking. Two ‘ smoke flaps ’ at the top of the tipi are adjusted with long poles. The tipi is moved every six months to prevent the ground underneath to grow naturally.

Outside a few naked people were waking up and were still laying in the grass. But there are limits to the ‘anything goes’ atmosphere. Some people are incredibly friendly, others are more suspicious of outsiders. And, announcing oneself as a journalist is never a good idea. A rather aggressive middle-aged man, seeing our camera, says: "You can’t take pictures without asking for a permission first". Tipi village is not a completely lawless village but, has its own take on what counts as a point of principle like any small society.

Photography © Emma Stoner

A ginger-haired freckle-faced, happy boy in his early 20s, who is called Breeze carrying water back from the well by bicycle when we met him. Breeze is one of the many children born genuinely in a tipi, but he had left for the city to study. After spending a couple of years around Spain, living in a similar hippy commune he ended up coming back to his family.

Another Tipi dweller we met, Liam - a half English and half Chinese boy born in the Tipi Valley, is composing music in his wooden cabin. He a stepson of one of the village’s original founders, Rik Mayes, lives next to his father’s caravan near the official entrance to the village.

He happily heads outside to eat ice-cream despite the rain. Aged eighteen, Liam travels to and from Swansea everyday to study. Some of the village children attend the local schools or are home-schooled by their parents under the annually inspection of the education authorities. The children’s language is to Welsh, which they learn at the Talley School. Most of the Tipi children are billingual but, Liam is not one of them.

Rik, now 63 years old, mentions: "The community is far more integrated nowadays - children attend the local schools and hitch hikers are ferried to and from Llandeilo.The last ten years, thankfully we have our own legislation, as my boy couldn’t even go to school when he was at the age of eleven", referring to the local’s wrath on their children, the first years they have established the community. Himself holds a degree in Theology from King’s College in London and as a professional vicar, conducts any occasional church services of the community.

In 1978 he was prosecuted for smoking grass, lost his vicar’s license and spent six months in prison. He has lived in Tipi Valley for more than 30 years, "it’s a tribal and wild commune, but it looks rather like a village with a different sense of the wider world. We ain't yearn for normality", he adds. A declaration that rather provoked us some amusement.

“It’s a tribal and wild commune, but it looks rather like a village”

Social Security scroungers?

"Over the years there have been hundreds of people come and go, but the population is stable the last twenty-five years. We are currently about 60 adults and 30 children. Over the past 35 years more than 90 babies were born in the Tipi Valley, though some of them were to families that came to the Valley specifically to give birth to their children. We own a valley of about 200 acres, 100 acres of which we own in common. The idea is that we live within Nature as a part of Nature, using what resources we need and without seeking to dominate over the environment". The early years were quite a challenge, "...we were an anarchistic community with a lot to learn. Our community was inundated with refugees, some whose negative dress code and behavior gave the whole Tipi Village a bad name", he adds. "The local farmers had genuine problems with us, trespassing their land to gather firewood".

The relationship that these communes have with the immediate environment around them could be easily troublesome. If they don’t contribute to the neighbor's welfare and so on, you can see how farmers could be rather suspicious about people like them. But, that has changed at Tipi Valley, and Rik explains: "Nowadays, we have a better relationship with the villagers. We are very grateful to our neighboring farmers John Williams of Blaen Waen and Ron Jenkins of Capel Hir in particular, for 'forgiving us our trespasses' and for the friendship they have shown us in recent years. The local community in Llandeilo, has stopped trying to take us down and actually it cooperates with us. They don’t care what we do or what we are planning to do, they just don’t want us to get any bigger", Rik concludes.

As time went by, Tipi Village become more tolerant to the mainstream lifestyle, and even have adopted some of its commodities. Considering the clash of cultures nowadays: "Certainly, now it is less of a problem because the difference in the lifestyle of the communities is much closer to the mainstream than was the case forty years ago", Rik agrees.

“Everyone takes care of his own finances. We are dependent upon making a living ourselves. The Valley people have a wide variety of trades and professions.”

There are certainly mixed reports about Tipi village. They used to hold free rave parties with drugs in full flow. They still celebrate but try to keep it lower key. Occupying the land without an official permission was another source of conflict in the early days and the community had to fight numerous legal battles to remain on spot. There was a time when the Tipi Valley hippies had a fractious relationship with the locals. At last, things are getting better and better at their end. Nowadays, the bureaucrats seem to have far less appetite for interfering with a community that has its origins in the Stonehenge free festivals of the 60s and 70s.

Rik clarifies: "Most of our land is quite legally lived on, for the 10 years change of rule relevant whether you apply for a Certificate of Lawful Use or not. The Council has no intention of trying to get rid of us anymore. Today most inhabitants sew their own canvases. I personally have accurate records of where every dwelling has been situated for the past 26 years if there is a need to prove it so".

And so, they survived with no external council-control or internal and hierarchies for more than three decades. There is, however, a single primary rule: to RESPECT EACH OTHER. Rik goes further: "We don’t have a leader. Being a leader is not a status here. We are all part of that leadership, but according to what we contribute. For instance, when we have complaints about something or someone, or a proposal to put it down, what we do is talk to people about it. And that’s how a democratic society should work I guess". Everyone takes care of his own finances. "We are dependent upon making a living ourselves, and the Valley people have a wide variety of trades and professions", reckons Rik proudly. There are from honey producers to tipi makers, yurt manufacturers and local schoolteachers in the community. Rik sums up, "in the early years we were ourselves refugees from the cities, and it is true that then most of us were dependent upon Social Security payments from dear Mrs Jones of Talley Post Office, in those days situated in Pretoria House, Talley."

It was then. that they were easily labeled by theri folks as social security scroungers. Those days of “Social Security handouts” are long gone, but they still have the opportunity to establish themselves, and thus remain very thankful.

Nowadays, residents are like anyone else, in paid work most of the time but claiming the standard child benefits and tax credits. "If you are self-employed with your particular trade or craft and are over 25 years old you will may be eligible for Working Tax Credit, an option some households go for, as the income you will generate yourself will most likely be more on a third world level compared to average British wages. Pension Credit is available for persons over 60, until the Government changes everything again", Rik adds. And he continues: "we never regarded ourselves as lazy hippies but pioneers of a new way of life, making as much use of opportunities offered to us as we could. We lived as simply and cheaply as possible, and all the money we saved was donated to our 'Land Fund', which we used to buy land that led to the birth of Tipi Valley". The 'Land Fund' continues to collect money for a hoped-for and important land purchase of neighboring Pistyll Gwyn cottage for the purposes of the community. Rik who found harmony with nature and is still loyal to his hippie ideals finally admits: "it is too late for me to move into a regular house, it wouldn’t feel right after so many years".

Back at the Big Lodge Tony and his girlfriend, are listening to a radio. They are sketchy about the past but say the met while being homeless, living on the streets somewhere in England. They had ended up at Tipi Valley mainly to join her mother. They have been staying at the Big Lodge for two months waiting for the right time to build their own dwelling. Most newcomers live in a tipi or yurt up to five years before considering a static dwelling such as a turf-roofed with mud-walled roundhouse. Caravans are not really an option except for travelling.

Tony is putting wood on the fire stove and the smoke from the fire rises up and waves around the top. "Tea anyone?", he screams to all the people who have gathered inside the Big Lodge.

“On a Saturday afternoon everyone sits in a lotus position around the fire to share tea and stories. ”

Photography © Debbie Bragg

Bureaucracy has no place here

They only payment to the state is about 4000 pounds per annum towards Council Tax of the various old stone built farmhouses on the land. Building of whatever material have to be maintained. Water has to be fetched and the firewood cut as there is no electricity and no gas. "You can not run out of firewood in the middle of a cold night, otherwise you would freeze to death", Tony tells cheerfully.

The tipis are lit by candles with torches as back-up for finding the outdoor toilets. Usually, they dig their own latrines for environmentally friendly waste disposal. Good hygiene is important and clothes are washed in hot soapy waters in their effort not to spread any illnesses. But it’s not power showers and automatic washing machines. There are many different approaches to washing, from year-round dips in icy-streams to tin baths. More conventional bathrooms are available during the winter in one of the farmhouse outbuildings.

But how independent are they of modern technology in this post-industrialized age?

Outwardly, they are living a surprisingly conventional existence, while always allowing life to be shaped by circumstances. "Don't think that we are a group of hippies, living off bulbs, and wearing clothes made of potato sacks", Zac utters and laughs loudly. Zac, whose father earns a living making tipis by exporting them all over the world, owns a car. The rest have laptops and once in a while head to the post office for a chat on Facebook with their families and friends. Most of the young children have their own gadget collections and are as eager as any other children of their age for the latest playstation 3. It seems almost impossible to be purely anti-capitalist. In sense you cant away from it. Actually when you try to be away from it you end up as a disconnected bubble from the rest of the world, which everyone knows, has some problems.

Henri a young man with long rasta hair, wearing jeans and a wool sweater, seems to be rather at peace with himself. "I have a college education. I am living like this by choice", he says to us. Today he isn’t working, he is just taking care of his tipi. Yesterday he spent watching his fire going out and then, he slept. There are many people alike Henri in the village and one could say that they are sleepwalking through their life under a tipi shelter.

Every Saturday late at night everybody goes to Jim’s cottage for the Jim Jams feast. Attended one of those Jim and Jam events that will forever be vividly imprinted in our memory. As we got there, after finishing our conversation at the Big Lodge, reggae music was playing. Everybody could join the musicians and themselves kept exchanging instruments. It was mesmerizing.

We contribute to the local economy and life, especially in the realm of folkmusic", says Rob a middle-aged white long white hair man who has been visiting the Tipi village for decades. And he adds: "I was 21 and still unsure of my place in the world. I was drinking and drugging way too much to cope with my insecurities. Taking the ‘magic bus' to the Tipi village, I hoped that I would maybe magically be healed". He regards himself a genuine hippie, chasing a dream and not the reality anymore.

Photography © Emma Stoner.

“On new moons, a sweat lodge party is held place, in a tipi filled with heated rocks to create a sauna. Clothes come off and the villagers jump inside. Spirituality is natural, mostly expressed in chanting and drumming at the sweat lodge (sauna) and at Big Lodge get-togethers.”

Lola has kept her a 70s’ style, like a remnant of old an era. She wants to go to Greece with her boyfriend, for the summer. They have been together for many decades, but were never faithful to each other. While mainstream couples struggle with monogamy, Lola and her husband have been changing partners consciously. They regard themselves as true ‘travelers’ and camp all around the world, discovering new places.

But, what are the consequences of being born here instead of the outside world?

Lottie, a young girl with blue-green eyes and a rather forced smile, says that she has lived there most of her life. "My childhood here was something special. We had a lot of freedom a lot of playground to grow up in. I learned earlier to handle the freedom within the limits you should have as a child". She now works in the Lllandeilo but always come home to to her tipi.

Breeze, on the other hand, confesses how much he misses a real house and warmer weather. Ishi Church, being a tourist by now, was born in a tipi, although chose not to move back after going off to university. "The tipi was a big part of my life and has shaped my current personality".

Hardly anybody spends more than a pound a day for food, and travel if not by caravan is always by thumb. Some of the residents are members of the Green Party and therefore fanatics of the 'small is beautiful' movement. Rik refers to the above: "There are families who live in the tipi village and are gradually becoming self-sufficient. They grow their own vegetables and bring up their own animals. People are already investing in solar panels and things. Particularly, twenty solar panels go for all the residents, whereas others survive only with the basics". "We are consuming less energy than the people living in the houses outside the village. We are not compromising as we have a low footprint anyways. Additionally, we are living somewhere that it is extremely, extremely beautiful", he looks up at us and smiles.

The overnight experience is a testament to Rik’s words: "You have to really want to come here, otherwise you would probably never make it. It's a survival lifestyle indeed", "however, when the sun comes out and you are living in the midst of wild nature, then you believe in Paradise on Earth".

Photography © Stacey HatfieldTipi Valley wilderness appeals to those bored or disgusted by man and his works. If offers not only an escape from society but also, is an ideal stage for the Romantic individual to exercise the cult that he makes of his own soul.

“Our experience of the Valley tells us though that Paradise is possible on Earth. And the Valley is a very magical place.”

Photography © Adam Elliott